As in the Game of Life activity, it can cut down on lots of direction and instructional time to use familiar games to support class concepts. This way, many if not all of the students will already know the rules of the game and can simply apply it to the new context without long explanations of procedures that can be difficult for non-auditory learners and those with attention problems.

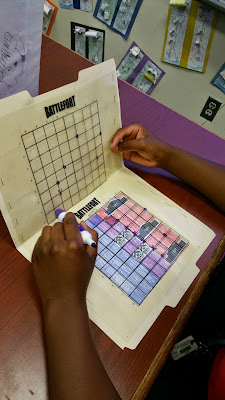

In order to support our study of the French and Indian War, we played our own iteration of the classic game Battleship. We substituted a land dispute for naval battle and placed forts and settlements in place of submarines and bombers.

The students designed their own boards based on the disputed territory of the French and Indian War and this was really intended to be the key "takeaway" of the game. I wanted the students to remember that these land claims in the Ohio River valley and Appalachian region were at the root of the conflict. Students also had to play the role of either Britain or France and place their forts and settlements according to the territories.

In order to play the game, each student received a grid with three cut-out forts and two settlements. Students should start in the top left corner and color in 25 blue squares to represent French territory. They can choose any 25 square, but they must all be contiguous. The same should be repeated with red squares starting the bottom right corner for British territory. Finally, disputed territory, or the 14 leftover squares in the middle area somewhere, will be colored in purple.

When students' boards are completely colored in, they may cut out the forts and settlements, then place them anywhere in their own country's territory or in the disputed territory. They cannot place forts or settlements in the other country's territory. Now they are ready to play.

Beforehand, I had prepared the game boards using some manila file folders, transparency film, and a stapler. For each student or board, print two copies of the labeled grid, shown below, on transparency film. Staple one copy to each side on the inside of the folder on the left and right edges only. This way, students can slide their boards in and out of the pocket. This is an inexpensive and easy way to to simulate a Battleship board.

When students are ready to play, their prepared grids should slide under the transparency. They can use dry erase markers to mark hits and misses with Xs and Os. I find that it takes students about 15-20 minutes to play one round and during one class period, we have time to switch players and play a second round.

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Complexity of Character: Teaching de las Casas to Middle Schoolers

One of the more difficult transitions of teaching history to middle schoolers is to leave behind the relatively simplistic, binary understanding of 'heroes.' In their elementary years, students tended to learn about historical actors as one-dimensional figures in a dichotomy of good and bad. One of the difficulties of doing 'real history' is to recognize that these historical actors are often products of their time and are never wholly good or bad.

I have found that one of the best ways to teach this complexity is with the figure of Bartolome de las Casas. The Spanish missionary came to the Americas in order to convert American Indians into Christians and save their souls. After arriving, however, and witnessing how they dying in droves from overwork, disease, and mistreatment, he wrote the Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies and advocated to the Spanish government to reform these practices.

As a result, many lessons and textbooks would like to place him firmly in the 'hero' category for being ahead of his time and advocating for the end of slavery. His place in history, however, is a bit more complex. In part, his advocacy for the Native American people was largely based in his perception of them as "lambs" and "innocents," a degrading if sympathetic image. He also is widely known to have encouraged the importation of African slaves from Seville to relieve the Amerindians of their labor, though it is likely he had a very different notion of slavery from what it would become in the Americas.*

So how do we explore this complexity of character with middle schoolers?

The Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies is a dense read and is written in language that can be cumbersome for many readers. With this in mind, I carefully selected a few excerpts from the text and put them into a worksheet with a right-hand column for glossing notes. In order to think critically about the primary source and reflect on de las Casas himself, I had the students complete a graphic organizer with a partner featuring some critical thinking questions to guide them.

The culminating assignment was a poster featuring the scales of justice and a two-column graphic organizer. Students reflected on the positive aspects of las Casas' legacy, as well as the negative legacy. The also leads students to begin considering what it means for a historical figure to be "of his or her time" and how historiography changes from one generation to the next.

*For further reading on Bartolome de las Casas, his shifting advocacy, and his perceptions of slavery, check out:

Clayton, Lawrence A. (2011). Bartolome de las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Zinn, H. (2003). A People's History of the United States: 1492 to Present. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

I have found that one of the best ways to teach this complexity is with the figure of Bartolome de las Casas. The Spanish missionary came to the Americas in order to convert American Indians into Christians and save their souls. After arriving, however, and witnessing how they dying in droves from overwork, disease, and mistreatment, he wrote the Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies and advocated to the Spanish government to reform these practices.

As a result, many lessons and textbooks would like to place him firmly in the 'hero' category for being ahead of his time and advocating for the end of slavery. His place in history, however, is a bit more complex. In part, his advocacy for the Native American people was largely based in his perception of them as "lambs" and "innocents," a degrading if sympathetic image. He also is widely known to have encouraged the importation of African slaves from Seville to relieve the Amerindians of their labor, though it is likely he had a very different notion of slavery from what it would become in the Americas.*

So how do we explore this complexity of character with middle schoolers?

The Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies is a dense read and is written in language that can be cumbersome for many readers. With this in mind, I carefully selected a few excerpts from the text and put them into a worksheet with a right-hand column for glossing notes. In order to think critically about the primary source and reflect on de las Casas himself, I had the students complete a graphic organizer with a partner featuring some critical thinking questions to guide them.

The culminating assignment was a poster featuring the scales of justice and a two-column graphic organizer. Students reflected on the positive aspects of las Casas' legacy, as well as the negative legacy. The also leads students to begin considering what it means for a historical figure to be "of his or her time" and how historiography changes from one generation to the next.

*For further reading on Bartolome de las Casas, his shifting advocacy, and his perceptions of slavery, check out:

Clayton, Lawrence A. (2011). Bartolome de las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Zinn, H. (2003). A People's History of the United States: 1492 to Present. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Thursday, January 22, 2015

New Perspectives on the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Underground Railroad

I have written about edX courses before, but now I have a renewed appreciation for the massive open online course (MOOC) movement now that I am fully immersed in a new course. For the past few weeks, I have been following (and loving) renowned historian Eric Foner's second module of the three-part series of courses on the Civil War and Reconstruction.

You can imagine my delight when just a few days ago, Eric Foner was a guest on NPR's Fresh Air and that he was discussing a topic somewhat outside the scope of the course, the Underground Railroad. His new book, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad mostly revolves around a few newly discovered sources from abolitionist and railroad operative Sydney Howard Gay.

His comments on the Underground Railroad were not only interesting, but they speak to the very tenets of "doing history" that historians relish, but few people truly understand. Many view the work of historians as either a stodgy pursuit of acquiring knowledge from dusty books, or, as a reflection of our digital- and science-driven times, as a pursuit of truth in a sea of misinformation. It certainly can be these things, but it is also a larger discourse of how history is shaped and narratives created and how the predominate narrative of an era defines the era itself.

In discussing the Underground Railroad we learn that the shifting understanding of what it was and its size and scope is similarly reflective of the times and scholars who study and create these narratives. How this story is told can be hugely symbolic of modern views on race politics and empowerment. The fact that so many narratives of the Railroad come from post-war memoirs and oral accounts is also telling about the nature of the story that persists.

While I certainly would like to report the most current research and discourse to my students when we cover topics such as this, I also hope to use overarching concepts like this to tackle more critical questions with my students. I want them to understand that history is not a set of definitive events, but instead a living creation that evolves along with the culture that consumes that history. Foner's new account of the Underground Railroad is just one piece of this conversation, and a good one at that.

You can imagine my delight when just a few days ago, Eric Foner was a guest on NPR's Fresh Air and that he was discussing a topic somewhat outside the scope of the course, the Underground Railroad. His new book, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad mostly revolves around a few newly discovered sources from abolitionist and railroad operative Sydney Howard Gay.

His comments on the Underground Railroad were not only interesting, but they speak to the very tenets of "doing history" that historians relish, but few people truly understand. Many view the work of historians as either a stodgy pursuit of acquiring knowledge from dusty books, or, as a reflection of our digital- and science-driven times, as a pursuit of truth in a sea of misinformation. It certainly can be these things, but it is also a larger discourse of how history is shaped and narratives created and how the predominate narrative of an era defines the era itself.

In discussing the Underground Railroad we learn that the shifting understanding of what it was and its size and scope is similarly reflective of the times and scholars who study and create these narratives. How this story is told can be hugely symbolic of modern views on race politics and empowerment. The fact that so many narratives of the Railroad come from post-war memoirs and oral accounts is also telling about the nature of the story that persists.

While I certainly would like to report the most current research and discourse to my students when we cover topics such as this, I also hope to use overarching concepts like this to tackle more critical questions with my students. I want them to understand that history is not a set of definitive events, but instead a living creation that evolves along with the culture that consumes that history. Foner's new account of the Underground Railroad is just one piece of this conversation, and a good one at that.

Friday, January 16, 2015

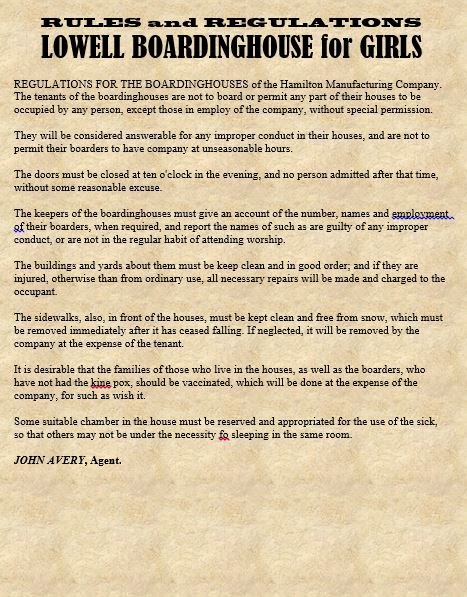

Imagining Life in the Mills

Because of the great success of our Roanoke Island mystery assignment, I wanted to give the students another authentic experience of sifting through documents and really "doing history." In our study of the early Industrial Revolution, I wanted to focus on the "mill girls" of Lowell, Massachusetts and their experiences in the factory textile mills.

To begin the assignment, I found some examples of modern child labor laws and had students write a journal entry about why they believe these laws exist and whether or not they agreed with them. Given that many of our students are nearing the age of legal employment with work permits in Pennsylvania, many of them came with background knowledge about what was required to enter the workforce.

To begin the assignment, I found some examples of modern child labor laws and had students write a journal entry about why they believe these laws exist and whether or not they agreed with them. Given that many of our students are nearing the age of legal employment with work permits in Pennsylvania, many of them came with background knowledge about what was required to enter the workforce.

Like in the Roanoke assignment, I compiled a dossier of documents from the time period including rule sheets for the employees of the mills and the boardinghouses where the girls lived. Students read a government report into health concerns of mill employees, as well as a letter based on the description of the mills in the historical fiction novel for young adults, Lyddie by Katherine Paterson. I was also able to find an authentic rule sheet for both the factory and the boardinghouse that would have been distributed to workers. I retyped it and laminated it for the students to peruse.

After reading through the dossier, the students compiled a three-column chart of notes. Once they have the initial information, the teacher can really guide this lesson into any assignment or skill-building exercise that the curriculum requires. Because there is so much flexibility in how these documents can be used and indeed I have used them differently throughout the years, I have posted images of my typed versions of the documents for classroom use. For copyright reasons, I will allow teachers to choose their own excerpts from Lyddie.

A complete transcript of this report can also be found on the University of Massachusetts, Lowell's library site here.

More primary source text from the Lowell mills can also be found here.

Friday, January 9, 2015

Classroom Performers

If you follow this blog at all, you know that much of my inspiration often comes from stories heard on NPR. This post is no exception. Recently, while running errands in the afternoon, I heard a story on All Things Considered about "teachers as performers" and the disparity between this reality and the extent to which we prepare teachers for this role in college and other degree programs.

In the story, teacher Amanda Siepiola describes channeling Bruce Springsteen and his seemingly effortless way of capturing a crowd of thousands. The story goes on to discuss the extent to which good teachers are not only fluent in curriculum, pedagogy, and content material, but also in performing.

This story struck me for three primary reasons. Firstly, I come from a family with more than a few devoted Bruce Springsteen fans. I have also felt many times that there was an element of performance and 'art' to the way that I teach, so the message of this story struck a chord. Finally, I felt a little more connected to this article since Bruce Lenthall, the executive director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at the University of Pennsylvania, was a professor of mine back when he was a visiting history lecturer at Bryn Mawr College.

Particularly in the comments section of the webpage for the story, many seem to have too literal an understanding of what exactly it is like and feels like to be both the "performer" and the student in the performance. Firstly, there is an implication in both the story and the comments that performances are one-way directional experiences and that, as a result, in order to consider a teacher a performer, we must be referring to a lecture-based, teacher-centered classroom. I don't believe that this really needs to be the case.

Speaking to this point, the example of Springsteen is particularly apt. When you see Springsteen, you don't watch him in wonder. He does more than just entertain you; you are part of the show. Otherwise reserved people can be seen dancing in the aisles. Fans bring posters with hundreds of non-Springsteen song titles, essentially challenging him and the E-Street Band to an impromtu jam session of Jackie Wilson's "Higher and Higher" or even "Santa Claus is Coming to Town." The audience watches Bruce and he plans the basic trajectory of the show, but the show changes based on the crowd and the location and the guidance of the audience.

Above is a photo, albeit a crummy cell phone picture, of a Springsteen show that I attended in 2012. It was his last ever show at Philadelphia's Spectrum before it was demolished, a fact that only added to the personal nature of the show. Bruce has banners emblazoned with his record-breaking number of sell-outs at the venue right along side retired player numbers. During each show, the house lights are turned on and the crowd is reminded that they are surrounded by "a few thousand of their closest friends." Minutes after this picture was taken, Bruce was running through the crowd, bringing fans on stage, and playing requests right from the crowd.

Perhaps this is a better description of the performance aspect of teaching. Outside the small minority of purely student-driven, inquiry-based classrooms (which also have their limitations as discussed here), the teacher brings a particular set of skills, experiences, and/or knowledge and guides the trajectory of the course based on specific curriculum and standards. The teacher's role is also not just to keep the kids "entertained," but also to engage and inspire.

Indeed even if a teacher does decide to embrace a methodology that shies away from lecture- or teacher-based instruction, it is clear that his or her enthusiasm will add interest and authenticity to the lesson, and perhaps this is just as much the so-called performance of teaching. Maybe the better question is, what does teaching look like without some aspect of performance? Regardless of the well-planned nature of the lesson or the background knowledge of the teacher, are these the lessons students view as 'boring?'

One thing is for sure -- teaching for me sure feels like a performance. I have spent time with my fair share of musicians given that my husband plays in a local metal band. These musicians often describe a unique feeling of performing that provides a heady feeling of accomplishment, but after the rush of wrapping up the show, they're wiped. This is in essence the late-night version of my teaching life.

When I do what I do, I feel absolutely in my element, like words and ideas are just flowing from me and I feel energized. As soon as the day is over, however, and I decompress and check emails, I am exhausted. And I don't think I am alone in this feeling. Being on is tiring and sharing your energy and creativity really takes it out of you.

For what it's worth, give yourself some credit! Here's to your inner-rockstar!

In the story, teacher Amanda Siepiola describes channeling Bruce Springsteen and his seemingly effortless way of capturing a crowd of thousands. The story goes on to discuss the extent to which good teachers are not only fluent in curriculum, pedagogy, and content material, but also in performing.

This story struck me for three primary reasons. Firstly, I come from a family with more than a few devoted Bruce Springsteen fans. I have also felt many times that there was an element of performance and 'art' to the way that I teach, so the message of this story struck a chord. Finally, I felt a little more connected to this article since Bruce Lenthall, the executive director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at the University of Pennsylvania, was a professor of mine back when he was a visiting history lecturer at Bryn Mawr College.

Particularly in the comments section of the webpage for the story, many seem to have too literal an understanding of what exactly it is like and feels like to be both the "performer" and the student in the performance. Firstly, there is an implication in both the story and the comments that performances are one-way directional experiences and that, as a result, in order to consider a teacher a performer, we must be referring to a lecture-based, teacher-centered classroom. I don't believe that this really needs to be the case.

Speaking to this point, the example of Springsteen is particularly apt. When you see Springsteen, you don't watch him in wonder. He does more than just entertain you; you are part of the show. Otherwise reserved people can be seen dancing in the aisles. Fans bring posters with hundreds of non-Springsteen song titles, essentially challenging him and the E-Street Band to an impromtu jam session of Jackie Wilson's "Higher and Higher" or even "Santa Claus is Coming to Town." The audience watches Bruce and he plans the basic trajectory of the show, but the show changes based on the crowd and the location and the guidance of the audience.

Above is a photo, albeit a crummy cell phone picture, of a Springsteen show that I attended in 2012. It was his last ever show at Philadelphia's Spectrum before it was demolished, a fact that only added to the personal nature of the show. Bruce has banners emblazoned with his record-breaking number of sell-outs at the venue right along side retired player numbers. During each show, the house lights are turned on and the crowd is reminded that they are surrounded by "a few thousand of their closest friends." Minutes after this picture was taken, Bruce was running through the crowd, bringing fans on stage, and playing requests right from the crowd.

Perhaps this is a better description of the performance aspect of teaching. Outside the small minority of purely student-driven, inquiry-based classrooms (which also have their limitations as discussed here), the teacher brings a particular set of skills, experiences, and/or knowledge and guides the trajectory of the course based on specific curriculum and standards. The teacher's role is also not just to keep the kids "entertained," but also to engage and inspire.

Indeed even if a teacher does decide to embrace a methodology that shies away from lecture- or teacher-based instruction, it is clear that his or her enthusiasm will add interest and authenticity to the lesson, and perhaps this is just as much the so-called performance of teaching. Maybe the better question is, what does teaching look like without some aspect of performance? Regardless of the well-planned nature of the lesson or the background knowledge of the teacher, are these the lessons students view as 'boring?'

One thing is for sure -- teaching for me sure feels like a performance. I have spent time with my fair share of musicians given that my husband plays in a local metal band. These musicians often describe a unique feeling of performing that provides a heady feeling of accomplishment, but after the rush of wrapping up the show, they're wiped. This is in essence the late-night version of my teaching life.

When I do what I do, I feel absolutely in my element, like words and ideas are just flowing from me and I feel energized. As soon as the day is over, however, and I decompress and check emails, I am exhausted. And I don't think I am alone in this feeling. Being on is tiring and sharing your energy and creativity really takes it out of you.

For what it's worth, give yourself some credit! Here's to your inner-rockstar!

Tuesday, January 6, 2015

Have you checked out Understood?

Understood is really intended as a resource for parents of students with learning differences, but it can be tremendously helpful for teachers, as well.

The site has information about learning disabilities, simulations to "see the world through your child's eyes," and tools and forums for parents. They offer an email newsletter that provides frequent updates about new material.

To illustrate how this can be useful for teachers, today's email update featured reviews of apps that are useful for students with various learning problems and attention issues. The slideshow is featured here.

Reaching students with learning and attention issues can be challenging, especially for the many teachers who are so-called neurotypical and have never experienced these problems. Understood is a great resource for understanding the way children learn and reaching out to others in the community for support and strategies.

The site has information about learning disabilities, simulations to "see the world through your child's eyes," and tools and forums for parents. They offer an email newsletter that provides frequent updates about new material.

To illustrate how this can be useful for teachers, today's email update featured reviews of apps that are useful for students with various learning problems and attention issues. The slideshow is featured here.

Reaching students with learning and attention issues can be challenging, especially for the many teachers who are so-called neurotypical and have never experienced these problems. Understood is a great resource for understanding the way children learn and reaching out to others in the community for support and strategies.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)